Life of Pi- Syndicated Feature by Mark Fisher

When the team staging Life of Pi arrive at Wales Millennium Centre on 17th October, they will bring along their own physiotherapist- just like a visiting football team.

And the physio will have their work cut out for them. This is a show staged by an elite squad who have some series lifting to do.

Life of Pi is the story of Piscine Molitor “Pi” Patel who finds himself lost at sea for 227 days in a lifeboat with only zoo animals for company.

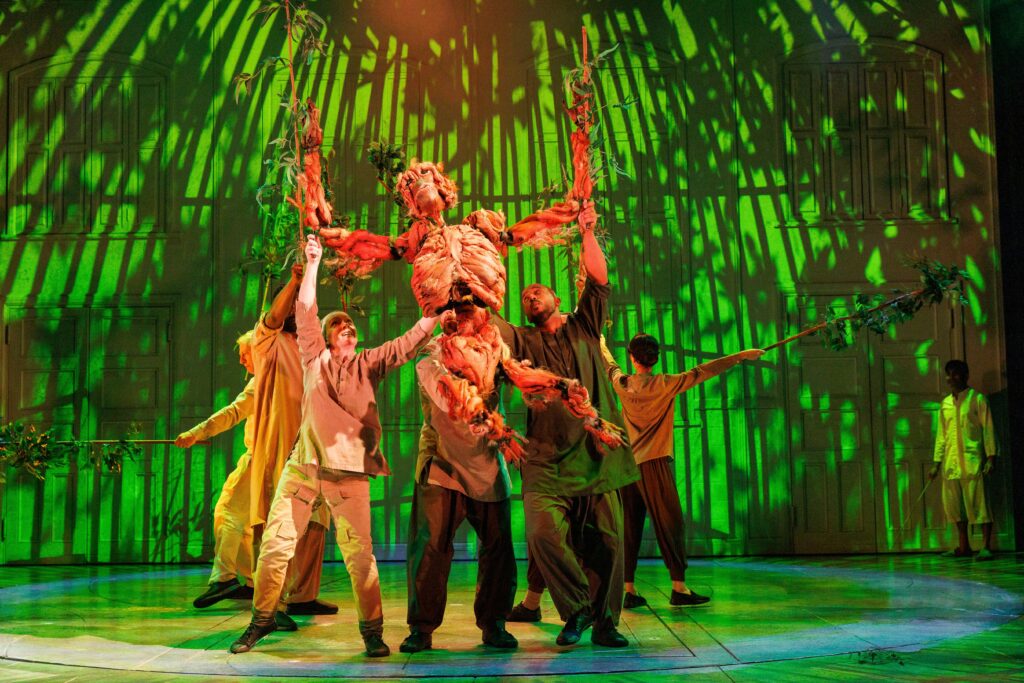

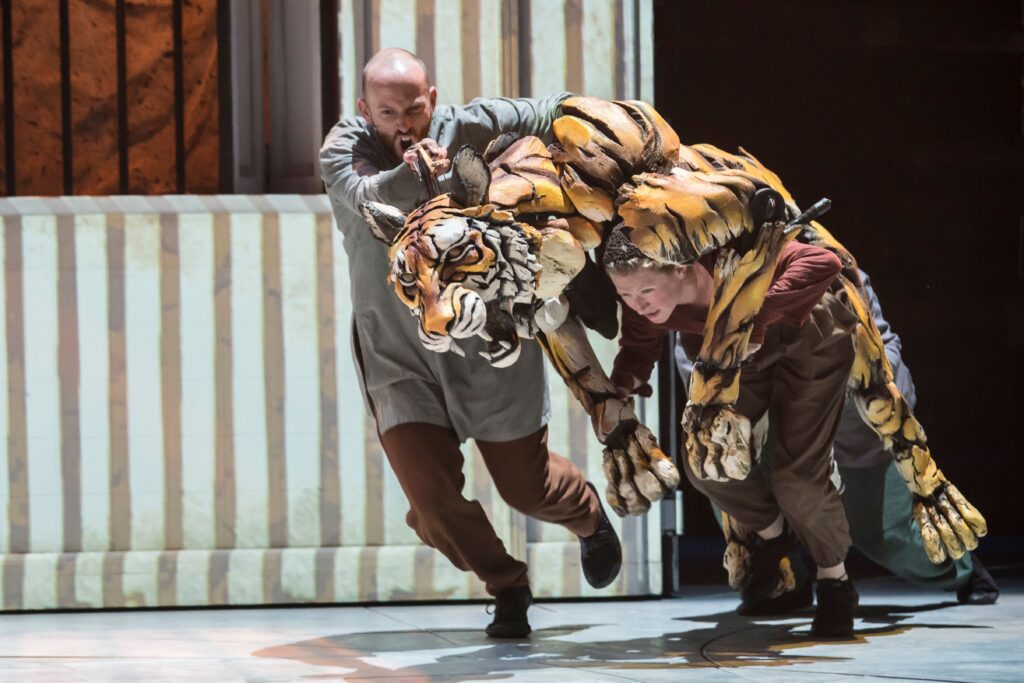

One of them is Richard Parker, a 450-pound Royal Bengal tiger. To bring the enormous creature to life takes seven puppeteers- and they need to be at the peak of physical fitness.

“I still go to the gym but I don’t lift as much because I know I’m gong to get a work-out during the show,” says Akash Heer, who manipulates the tiger’s head. “My stamina has definitely improved.”

“It’s an athletic piece of physical theatre,” says Max Webster, the director, whose show won five Olivier Awards in the West End and three Tony Awards on Broadway.

“It’s demanding, physical and extreme. The extremity of the physical challenges are linked to the excitement of what you’re watching on stage.”

But it is not only the show’s physical demands that are daunting. It took a special type of bravery to adapt Yann Martel’s magic-realist novel. Aside from the book’s meditations on philosophy and religion, its cast of characters include a hyena, a zebra and an orangutan.

And it is set in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Yet when she was asked to adapt it by producer Simon Friend, playwright Lolita Chakrabarti jumped at the chance.

“I loved the book and without knowing how, I was like, ‘Yes, please’,” she says. “I like to write a first draft on my own without anyone else creative attached. I didn’t have any idea how amazing the puppets would be or how they would evolve, but in terms of representing animals, I knew puppetry would be the way.

“Simon and I had this conversation where we said, ‘We’ve got War Horse on one side and Lion King on the other, so what do we do in between?'”

Before that question could be resolved, she was free to use her imagination. That meant writing parts for the non-speaking animals as well as for the people.

“It was all about the story,” says Chakrabarti. “Everything starts and finished with the script. It is key that you write in the puppetry elements. You need the beats in the script so the tiger can have the progression it needs. You have to have the logic and the intent and it doesn’t matter whether people are speaking or not.”

Even at the very earliest try-out, she had an inkling this was something special. The puppet designers Finn Caldwell and Nick Barnes had brought in a prototype tiger to test on a couple of scenes.

“It was literally a foam head on a spine with legs,” says Chakrabarti. “And it was magic even with that prototype puppet that had nothing to it. From that moment, it was a whole new thing.”

Her instinct was right. From the first dress rehearsal at the Sheffield Crucible in 2019, the audience gasped and rose to their feet.

It duly raked in the five-star reviews. One critic called it “a triumph of transformative stagecraft”.

Acclaimed runs in London and New York followed. Now, after the current 12-month tour of the UK, it has its sights set on Europe and Australia.

“There’s nothing like praise to make you up your game,” says Chakrabarti. “If someone says it is amazing you say, ‘Ok, how can I make it better?’ We’re all pushing the boundaries. It’s really exciting.”

How does Chakrabarti account for such phenomenal success? “Part of the reason people are so thrilled is you look at this cast as they come on stage at the end and you say, ‘Oh my God, you did all of that!'” she says. “There are not that many of them for the amount of storytelling that goes on. Every single one of them works their socks off.

“There’s also something about the story that brings people in. That’s testament to Yann Martel’s universal truths. He’s talking about survival, loss, struggle, metaphorical shipwreck as well as real shipwreck, what keeps you going in life, faith, people and love. These are things that have affected everybody no matter where you’d from or what you’ve been through.”

Director Max Webster was similarly excited by the prospect of staging the Man Booker Prize-winning novel. “I’ve always been interested in putting impossible things on stage,” he says. “You can stage anything: climbing a mountain or fighting a tiger in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. That also has a political link to the book: that imagination is possible and you can imagine a better society or a better world.”

In the theatre, the audience becomes part of the game of make-believe. “The show asks the audience to imagine along with it,” says Webster. “A puppet is not as realistic as CGI but, weirdly, because our imagination is involved, it’s like a hand being stretched out to us and the tiger becomes more real.”

Crucial in realising the ambitions of Chakrabarti and Webster is Finn Caldwell, the movement and puppetry director. Thanks to his high-precision work, the tiger seems to be every bit as real as Divesh Subaskaran, the actor playing Pi, a role alternated by Adwitha Arumugam at certain performances.

Caldwell has been thrilled to watch the production go from strength to strength as his colleagues have built on their triumphs.

“You learn like a musician,” says Caldwell, who previously worked on War Horse. “People get better and better at their instruments. The depth of understanding and the richness of their performance is extraordinary.”

Like playing a musical instrument, the puppeteers must follow a tightly choreographed physical score, making it their own as they master it. To bring a tiger to life, they must focus on every pulse, breath and muscle movement.

“There’s a story for the animals that runs like an undercurrent to the script,” says Caldwell. “We need to know precisely the physics of each moment- this paw hits the face and does this- but also every twitch of its paws, every flick of its tail is communicating some kind of thought or emotion.”

With all its puppetry and magical transformations, the play is not for the literal minded. The appeal is in the uncertain ground between the real and imagined.

“Despite working on it for four years, I still don’t really know what it’s about,” says Webster. “Is the relationship between a person and a tiger about two types of animal, a story about biology, is it a metaphor for human spirit, for adversity, for cosmic balance? I don’t really know. The reason it keeps working is it isn’t completely explainable. It allows audiences to think around it.”

Chakrabarti agrees. “When I read the novel I remember loving it and thinking, ‘What actually happened at the end?'” she says. “Was it the animals or was it the people? What does it mean? Yann Martel strikes a delicate balance because he keeps everybody leaning forward and questioning, ever curious about what actually happened.”

Now with the cumulative experience of its runs in Sheffield, London and New York, Life of Pi is as good as it has ever been.

“Audiences around the country will get to see something every bit as exciting as the show that was in the West End,” says Webster. “It’s a brilliant cast and a brilliant team and the spectacle is still going to be there. I’m thrilled we’ve been able to maintain the integrity of the show while brining it to all these beautiful places.”

Life of Pi, THEATRE, CITY, DATE. Details: https://lifeofpionstage.com/